Fat diseases: why this term is confusing and why it matters after 35

After about 35, fat distribution often shifts even if your weight stays similar. More fat may settle around the abdomen, and that matters because visceral fat (fat stored around internal organs) is more strongly linked to insulin resistance, abnormal lipids, and fatty liver than fat stored under the skin.

The tricky part is that many fat-related diseases start silently. You can have rising triglycerides, prediabetes, or early fatty liver with no clear symptoms. That is why a shortcut-friendly understanding of what “fat diseases” includes, and what to screen for, can save you time and stress.

What you’ll get in this guide:

- Clear definitions of what people mean by “fat diseases”

- A quick list of the most common fat-related diseases and conditions

- A practical screening pathway and action plan to discuss with your clinician

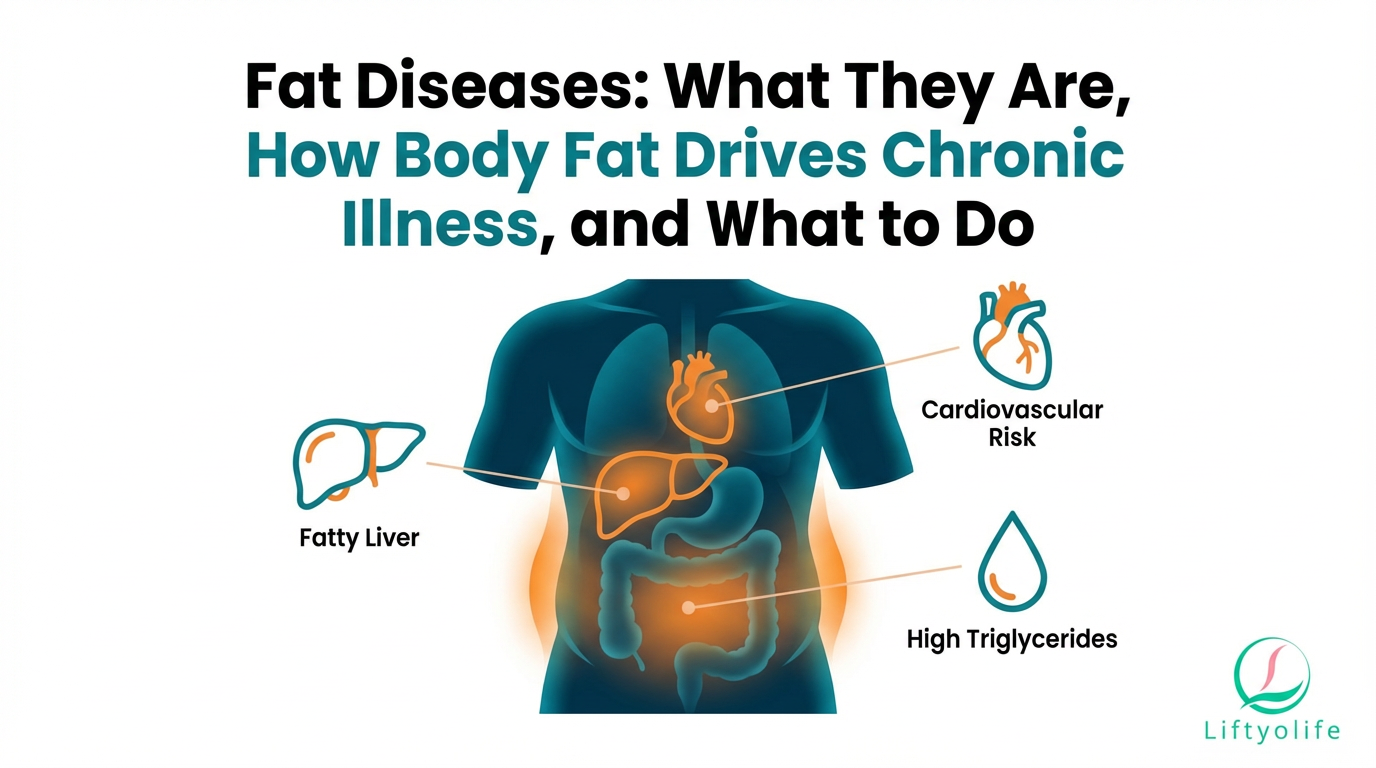

What are “fat diseases”?

“Fat diseases” is not a formal diagnosis. It usually refers to conditions linked to excess body fat, especially visceral fat, fat buildup in organs (such as fatty liver disease, now often called MASLD), and abnormal blood fats (dyslipidemia like high triglycerides or LDL). Visceral fat is riskier because it is metabolically active and closely tied to inflammation and insulin resistance (AHA).

What people usually mean:

- Diseases worsened by excess body fat (for example, type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure)

- Visceral adiposity (central obesity) that raises cardiometabolic risk

- Fatty liver (MASLD/MASH under the newer “steatotic liver disease” terminology)

- Dyslipidemia (high triglycerides, high LDL cholesterol, low HDL)

- Obesity: excess body fat that raises health risk.

- Visceral adiposity: belly fat around organs.

- Metabolic syndrome: a cluster of cardiometabolic risks.

- Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: impaired glucose control and insulin resistance.

- Dyslipidemia: high triglycerides/LDL or low HDL.

- High blood pressure: persistently elevated blood pressure.

- MASLD: fatty liver linked to metabolic risk factors.

- Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: plaque-building artery disease risk rises.

- Obstructive sleep apnea: airway collapse during sleep, worsened by weight and neck fat.

- Osteoarthritis: joint wear and inflammation, often worsened by higher load.

These conditions commonly overlap. That “clustering” is exactly why belly fat, labs, and liver health are often discussed together.

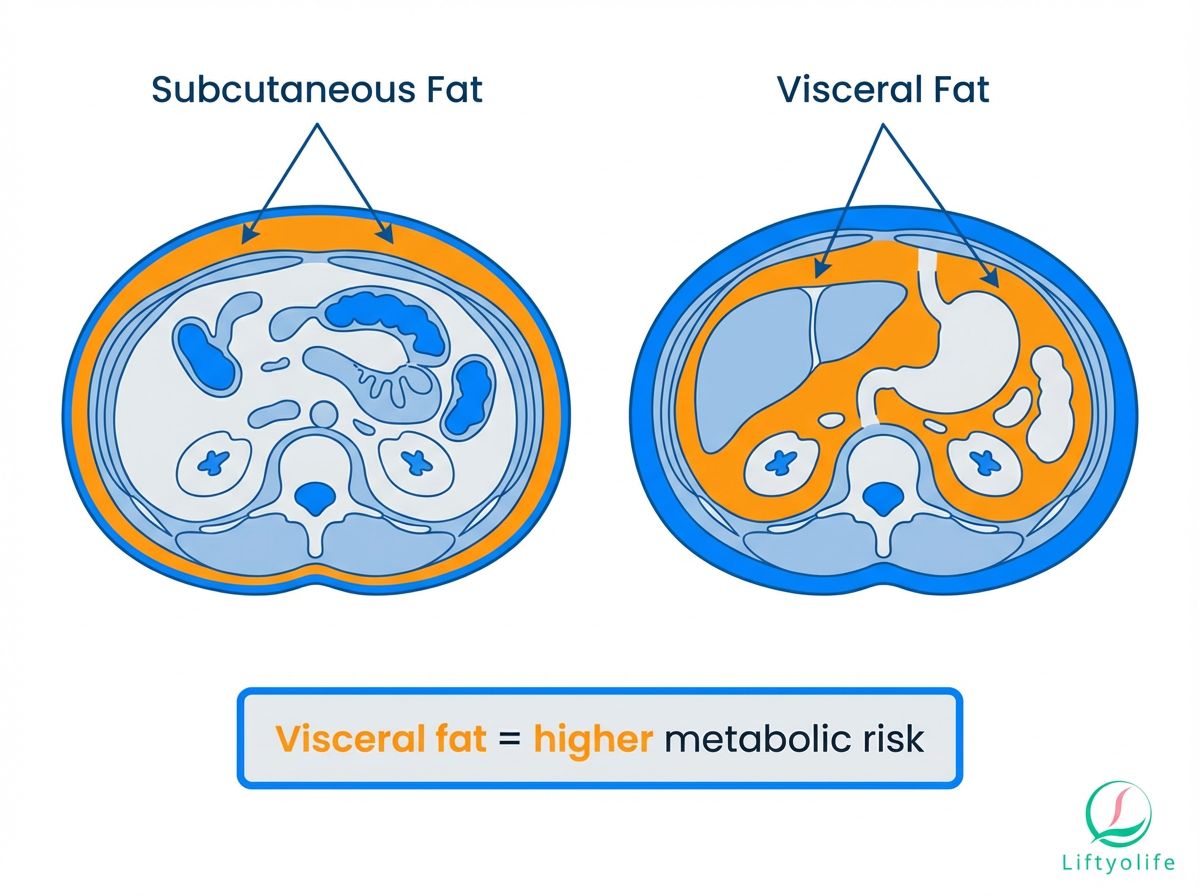

Why body fat can become harmful: visceral fat vs subcutaneous fat

Subcutaneous fat is stored under the skin (for example, hips, thighs, or just beneath belly skin). Visceral fat is stored deeper in the abdomen, wrapped around organs. The key point is not that one is “good” and the other is “bad”, it is that visceral fat is more strongly linked to cardiometabolic risk.

What visceral fat tends to do:

- Promotes insulin resistance, making glucose harder to control

- Drives chronic low-grade inflammation (a risk amplifier)

- Worsens blood lipids, often raising triglycerides and lowering HDL

- Increases risk of MASLD (fatty liver linked to metabolic dysfunction)

- Raises cardiometabolic risk even when BMI is “normal” (sometimes called “normal-weight metabolic obesity”)

In practice, this means BMI can be useful context, but it does not fully describe risk. Waist size, blood pressure, and labs often tell a clearer story.

Who is most at risk after 35?

Use this as a quick self-check. If you check 3+ boxes, consider basic screening labs (and bring this list to your next visit).

Lifestyle and habits

- [ ] Most meals are ultra-processed (packaged snacks, sugary drinks, fast food)

- [ ] You sit most of the day and rarely get sustained walking

- [ ] You do little or no strength training

- [ ] You sleep under ~7 hours most nights or have irregular sleep timing

- [ ] You snore loudly or feel sleepy during the day

- [ ] You drink alcohol most days, or you suspect alcohol worsens cravings/sleep

- [ ] Chronic stress and “always on” schedules are the norm

Medical and life-stage factors

- [ ] Menopause transition, perimenopause, or low testosterone symptoms (talk to a clinician)

- [ ] History of gestational diabetes or current PCOS

- [ ] Hypothyroidism (or symptoms that warrant evaluation)

- [ ] Family history of type 2 diabetes, early heart disease, or high cholesterol

- [ ] Medications that can affect weight or lipids (for example, some steroids, antipsychotics, and some antidepressants, ask your prescriber)

Ethnicity can influence risk at a given BMI or waist size, but it is not destiny. The safest shortcut is still the same: measure waist, check blood pressure, and get the core labs.

Fat diseases at a glance (what it is, key sign, first step)

| Condition | What it is | Key sign | First step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visceral adiposity | Deep belly fat | Waist increasing | Measure waist + labs |

| Metabolic syndrome | Risk-factor cluster | 3+ abnormal markers | Address lifestyle + meds |

| Dyslipidemia | Abnormal lipids | High TG/LDL, low HDL | Lipid panel + plan |

| MASLD | Liver fat + metabolic risk | ALT/AST or imaging | Risk score + imaging |

| Sleep apnea | Breathing pauses in sleep | Snoring, daytime sleepiness | Sleep study referral |

When it’s urgent: chest pain, severe shortness of breath, fainting, stroke symptoms, jaundice, vomiting blood, black stools, or severe abdominal pain. See the red-flag section below.

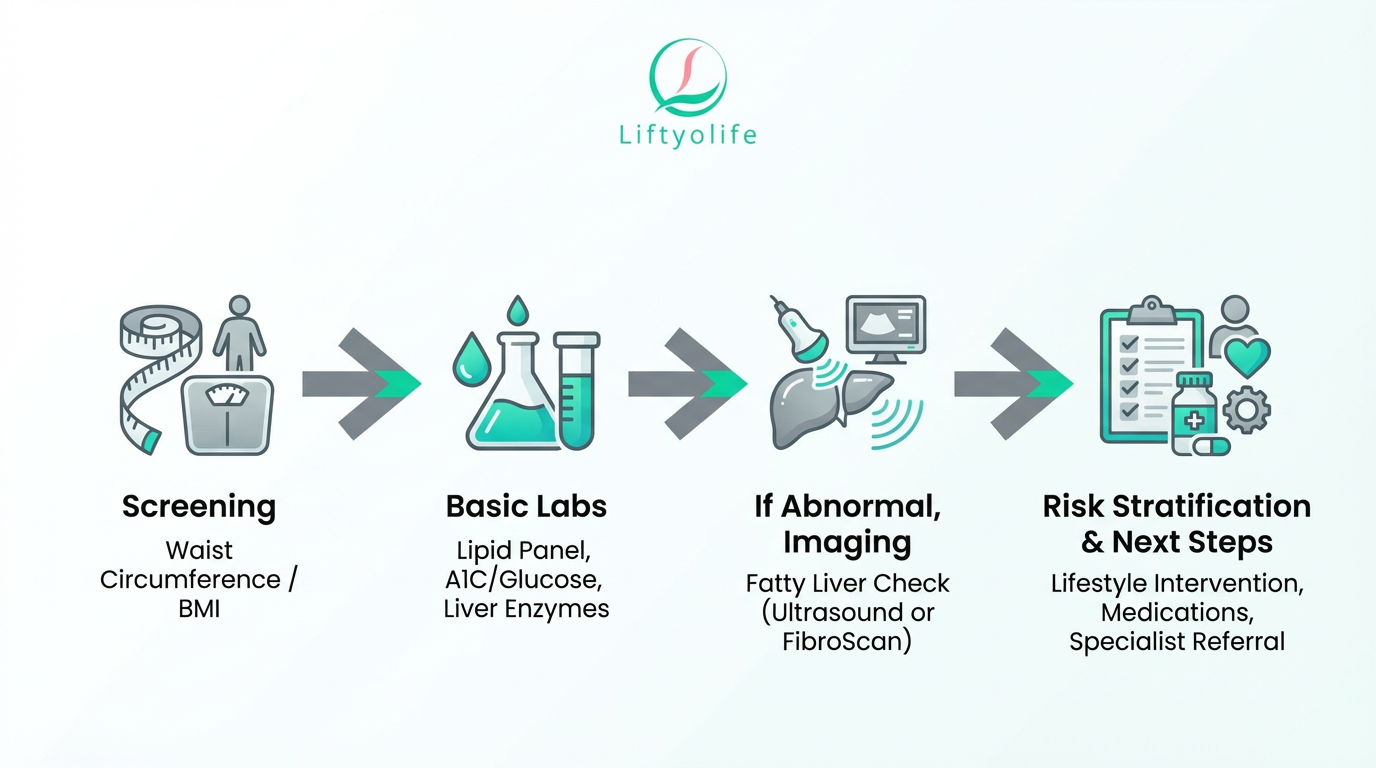

Here is a practical pathway you can discuss with your clinician. The goal is not to self-diagnose, but to make sure the “silent” risks are not missed.

- Start with measurements (the 2-minute screen)

- Waist circumference (a proxy for central obesity/visceral fat)

- Blood pressure

- Weight and BMI as context (helpful, but not the whole story)

- Core labs (the common “fat disease” labs)

- Lipid panel: LDL, HDL, triglycerides

- Glucose testing: fasting glucose and/or A1C

- Liver enzymes: ALT and AST (not perfect, but a common starting point)

- If risk is elevated, assess fatty liver and fibrosis risk

- Liver imaging: ultrasound can detect steatosis; FibroScan (transient elastography) estimates liver stiffness and fat

- Simple fibrosis risk tools: FIB-4 uses age, AST, ALT, and platelets to estimate fibrosis risk and help decide who needs further testing (AASLD)

- Advanced body-fat testing is optional

- CT or MRI can quantify visceral fat, but they are usually not necessary for routine risk management.

- If you want more detail about body composition, DXA scans are one option to discuss.

Bring this list to your appointment:

- Waist measurement and trend (last 6 to 12 months if you know it)

- Home blood pressure readings (if available)

- Ask for: lipid panel, A1C or fasting glucose, ALT/AST

- If liver risk is a concern: ask whether FIB-4 and ultrasound or FibroScan make sense for you

- Symptoms to mention: snoring, daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, fatigue, right upper abdominal discomfort (not specific, but worth noting)

NAFLD is now called MASLD: what changed

You will still see the term NAFLD (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) online, but many medical groups now use MASLD (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease). Likewise, NASH has been updated to MASH (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis). These updates were proposed to reduce stigma and better reflect the metabolic drivers of liver fat (NIH/PMC; AAFP; AASLD).

You may also see the umbrella term steatotic liver disease (SLD), which includes different causes of liver fat, including metabolic and alcohol-related patterns.

What this means for patients:

- You can ask about liver fat and fibrosis risk even if your chart still says “NAFLD.”

- The focus is on metabolic risk factors (glucose, lipids, blood pressure, waist), not just a name.

- If alcohol intake is part of the picture, clinicians may use newer subcategories like MetALD in some settings (AASLD).

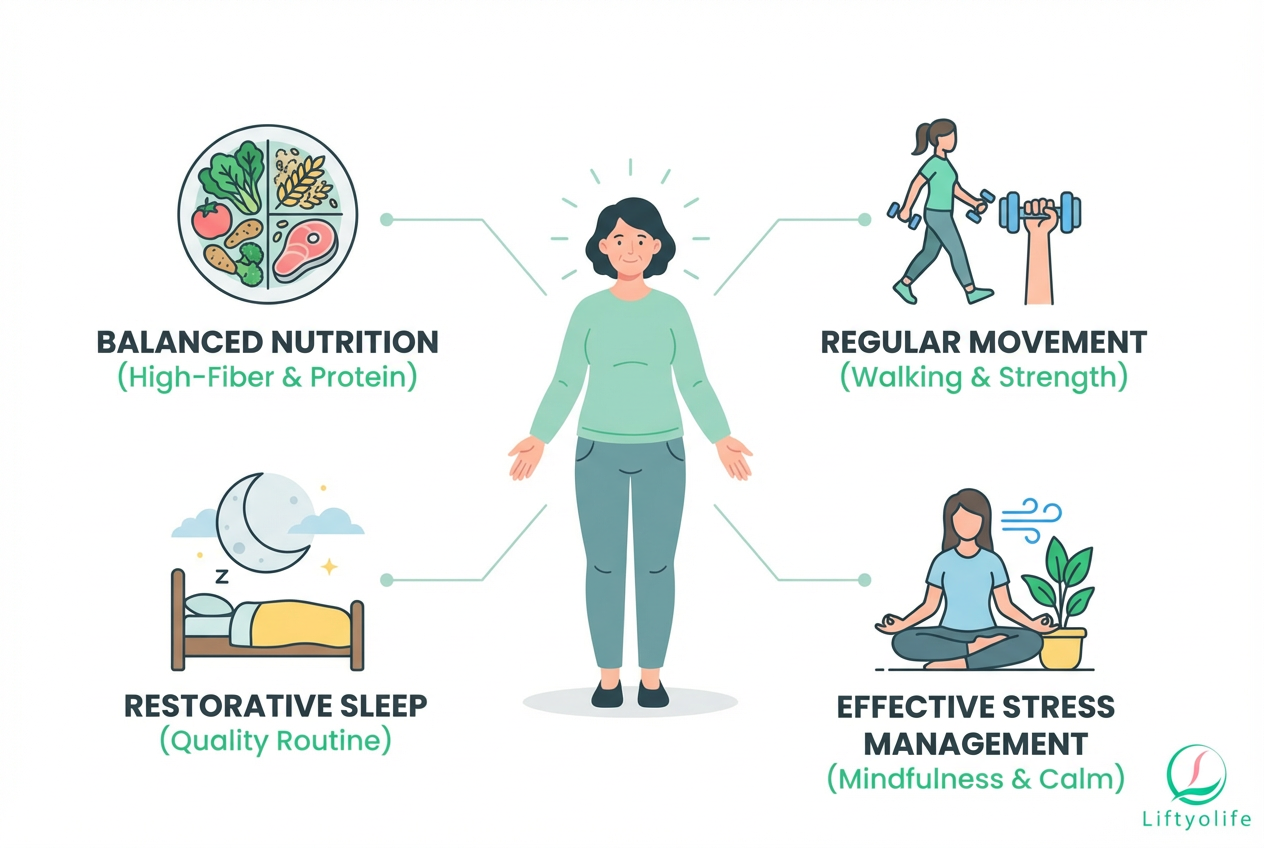

What to do about it: the simplest plan to lower visceral fat and chronic disease risk

Start here this week (pick what is realistic and repeat it):

- Eat protein + fiber at most meals (for example: Greek yogurt + berries, eggs + vegetables, beans + salad)

- Build a walking baseline of 7,000 to 8,000 steps/day (adjust for your joints and schedule)

- Do strength training 2 to 3 times/week (full-body, simple progression)

- Add 2 short cardio sessions (10 to 20 minutes) if you are currently sedentary

- Keep a consistent sleep window and aim for 7 to 9 hours

- If triglycerides or liver enzymes are high, reduce alcohol and avoid “saving drinks” for the weekend

- Set one “default” weekday breakfast and lunch to reduce decision fatigue

- Recheck key labs in 8 to 12 weeks after changes (timing varies by clinician and meds)

On Liftyolife, you can also follow our step-by-step guides to reduce visceral fat safely.

Nutrition

If you only do two nutrition changes, make them these:

- Prioritize protein to support muscle and appetite control.

- Increase fiber (beans, lentils, oats, vegetables, berries) to improve fullness and cardiometabolic markers.

Practical targets you can actually use:

- Add a protein anchor at each meal (eggs, fish, chicken, tofu, Greek yogurt, beans).

- Add one high-fiber food per meal (vegetables, beans, whole grains, berries, chia).

- If triglycerides are high, reduce sugary drinks, desserts, and refined carbs first. Those are common drivers.

- If MASLD is a concern, ask your clinician about an overall calorie deficit approach. AASLD notes weight loss improves steatosis and liver inflammation in a dose-dependent way (AASLD).

Evidence-based expectation setting: many guidelines and reviews note that ~3% to 5% weight loss can improve liver fat, while ~7% to 10% is often associated with broader improvements in steatohepatitis features (review evidence summarized in NIH/PMC; AASLD).

Movement

For visceral fat and metabolic syndrome risk, the “best” routine is the one you will repeat.

- Walking: build toward a daily baseline. If 8,000 steps is too much today, start with your current average + 1,000 steps/day.

- Strength training: 2 to 3 days/week, focusing on large muscle groups (squat pattern, hinge pattern, push, pull, carry).

- Cardio: add 10 to 20 minutes at a comfortable pace and progress gradually.

If you want a simple place to begin, this guide to strength training explains a beginner-friendly schedule, and this breakdown on adding cardio to reduce belly fat covers low-impact options.

Sleep and stress

Poor sleep and chronic stress can raise cravings, lower recovery, and worsen glucose control. If you suspect sleep apnea (snoring, gasping, daytime sleepiness), treat that as a medical issue, not a willpower issue.

Try this for 14 days:

- Fixed wake time within a 1-hour window

- No caffeine after lunch

- 10 minutes of downshift time (stretching, quiet walk, breathing)

- Dark, cool room and consistent bedtime routine

Medications

Lifestyle is foundational, but it is not the only tool.

Depending on your labs and overall risk, a clinician might discuss:

- Statins or other lipid-lowering therapy for high LDL or elevated ASCVD risk

- Blood pressure medication when lifestyle alone is not enough

- GLP-1 receptor agonists or other weight-loss/diabetes medications when appropriate and safe

If you are unsure what applies, ask: “Based on my numbers, what is my heart-risk and liver-risk, and what treatments are most evidence-based for me?”

When to see a doctor

This article is educational and not personal medical advice. If you are worried or worsening quickly, get medical care.

Emergency now

- Chest pain, pressure, or pain radiating to arm/jaw

- Severe shortness of breath or blue lips

- Fainting, confusion, or sudden severe weakness

- Signs of stroke (face droop, arm weakness, speech trouble)

- Jaundice (yellow skin/eyes), severe confusion, or rapidly worsening swelling

- Vomiting blood or black, tarry stools

- Severe abdominal pain, especially with fever or persistent vomiting

Schedule soon

- Consistently high home or clinic blood pressure readings

- Abnormal lipid panel, A1C, or liver enzymes

- Loud snoring, gasping, or excessive daytime sleepiness

- Rapidly increasing waist circumference with fatigue or low exercise tolerance

Less common “fat diseases”: disorders of fat tissue

Sometimes people use “fat diseases” to mean disorders of the fat tissue itself, not the common cardiometabolic conditions above. Two examples you may see mentioned are lipedema and lipodystrophy.

These are different from general obesity. They often involve unusual fat distribution, pain, or metabolic complications that do not match what you would expect from weight alone. Diagnosis and treatment require clinician evaluation, sometimes with a specialist.

Signs that warrant evaluation:

- Disproportionate fat accumulation (for example, legs enlarging with relatively smaller upper body)

- Tenderness, pain, or easy bruising in fatty areas

- Swelling that does not behave like typical fluid retention

- Unusual loss of fat in certain areas or very abnormal fat redistribution

Frequently Asked Questions

What are “fat diseases”?

“Fat diseases” is a broad, non-medical phrase. People often mean diseases linked to excess body fat (especially visceral fat), fatty liver (MASLD), or abnormal blood fats (cholesterol and triglycerides). Less commonly, they mean adipose-tissue disorders like lipedema or lipodystrophy.

What diseases are caused or worsened by excess body fat?

Common examples include type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia (high triglycerides/LDL or low HDL), MASLD, sleep apnea, and osteoarthritis. These conditions often overlap, so improving one risk factor can help several.

What is MASLD (fatty liver) and is it serious?

MASLD is the updated name that replaced NAFLD and refers to liver fat plus cardiometabolic risk factors. It can progress to MASH (inflammation) and sometimes fibrosis or cirrhosis, but many cases improve with early lifestyle changes and risk-factor control (AASLD, NIH/PMC).

Ask about waist circumference and blood pressure, plus a lipid panel (LDL, HDL, triglycerides), glucose testing (fasting glucose or A1C), and liver enzymes (ALT/AST). If liver risk is elevated, ask whether FIB-4 and liver imaging (ultrasound or FibroScan) are appropriate.

How much weight loss actually helps fatty liver and metabolic risk?

Evidence summarized in major reviews suggests roughly 3% to 5% weight loss can reduce liver fat, while 7% to 10% is often linked to bigger improvements in steatohepatitis features (NIH/PMC; AASLD). Strength training, better food quality, and improved sleep can also improve markers even before large scale changes.

Conclusion

Fat diseases is an informal phrase that usually points to a small group of connected problems: visceral fat risk, abnormal blood fats (dyslipidemia), and fatty liver (MASLD). The fastest safe next step is simple screening, waist and blood pressure plus a lipid panel, A1C, and liver enzymes, followed by a realistic plan you can repeat for 8 to 12 weeks.

References, medical review, and update policy

Last reviewed: 2025-12-19.

Update policy: The Liftyolife editorial team updates this guide as terminology and guidelines change.

References:

- No More NAFLD: The Term Is Now MASLD (NIH/PMC), overview of the renaming and rationale.

- New Year, New Name: NAFLD becomes MASLD (AAFP), primary-care explanation of updated terminology.

- AASLD: New MASLD Nomenclature, society overview of the updated terms.

- AASLD Practice Guidance: Clinical assessment and management of MASLD, guidance on evaluation and management.

- AHA Scientific Statement on Metabolic Syndrome, criteria and cardiometabolic risk framework.

- MASLD/NAFLD information (British Liver Trust), patient-friendly overview.

Disclaimer: This article provides general education and is not medical advice. If you have symptoms, abnormal labs, or urgent warning signs, seek professional care promptly.